Soil: Earth’s Living Tapestry

Beneath our feet lies an intricate tapestry of life, teeming with activity: soil. Often overlooked, the health and complexity of this living canvas significantly influence the sustainability of life as we know it (Lavelle and Spain, 2001). Soil ecology delves deep into this tapestry, studying the interactions between soil-dwelling organisms and their environment. The importance of this discipline is monumental, revealing how different organisms contribute to nutrient cycling, soil formation, and overall ecosystem functions (Bardgett, 2005).

The Day in a Life of a Soil Ecologist

Soil ecologists unravel the mysteries of soil ecosystems. Their endeavors range from microscopic analyses of soil microbes to broader studies addressing the soil’s impact on climate. Here’s a glimpse into their typical day:

Fieldwork: They might be collecting soil samples, setting up experiments, or taking environmental measurements (Wardle, 2002).

Laboratory Analyses: They delve into soil samples, identifying organisms, or measuring soil properties. They might use everything from basic microscopy to advanced methods like DNA sequencing (Fierer & Jackson, 2006).

Data Analysis: A lot of their time goes into analyzing data, using statistical software, and even crafting mathematical models to predict soil processes (Manzoni & Porporato, 2009).

Writing & Publishing: Like many scientists, they share their findings through scientific papers, enhancing the collective knowledge of the community (Bardgett, 2005).

Whereas the studies of soil ecologists may range in focus–say from examining agricultural practices’ impacts on soil health to exploring soil organisms’ roles in climate change (Doran & Zeiss, 2000; Six et al., 2002)– the results can benefit various sectors, from academia and government agencies to the private sector and non-profits.

See the video below for an interview with soil ecologist Dr. Yamina Pressler.

The Soil’s Biodiverse Orchestra

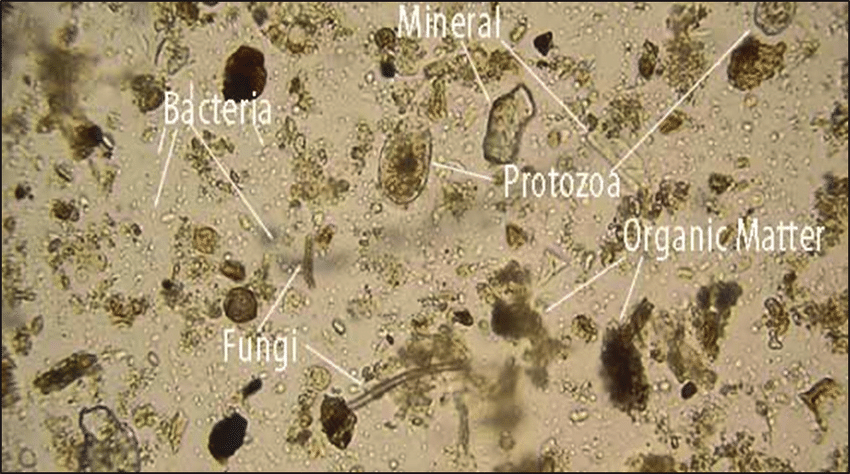

Imagine this: a single gram of soil could be bustling with up to a billion bacteria (Whitman et al., 1998). The soil is a realm of staggering diversity: bacteria, fungi, protozoa, nematodes, and many more. They all dance in a complex web of life, supporting functions like decomposition, nutrient cycling, and disease suppression (Bardgett and van der Putten, 2014).

In harmony, their collective efforts sculpt the soil. Diligent earthworms, for instance, burrow, aerating the soil and aiding water infiltration. Fungi, with their hyphal networks, bind soil particles, fortifying the soil structure (Ritz & Young, 2004). Some soil warriors even defend against plant diseases. We see this in certain strains of bacteria and fungi. For example, the fungus Penicillium chrysogenum produces antibiotics, effectively staving off pathogens, serving as nature’s own pest management system (Mendes et al., 2011).

Soil: Our Climate Guardian

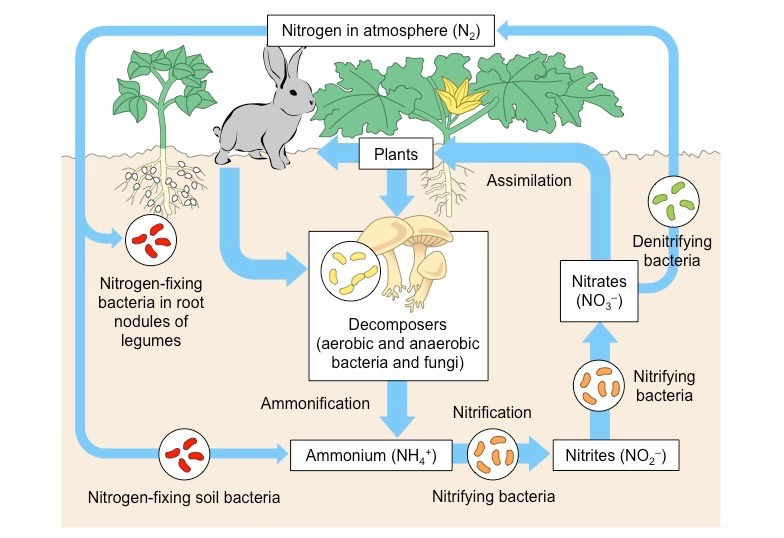

Soil biota play pivotal roles in the cycling of essential elements like carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus (Coleman et al., 2004). Bacteria and fungi act as recyclers, breaking down organic matter and releasing nutrients. Some bacteria, the nitrogen-fixers, even draw nitrogen from the air, converting it into a plant-friendly form (Vitousek et al., 2002). See the image below for a representation of the nitrogen cycle, emphasizing the role of soil organisms (Source: Bioninja).

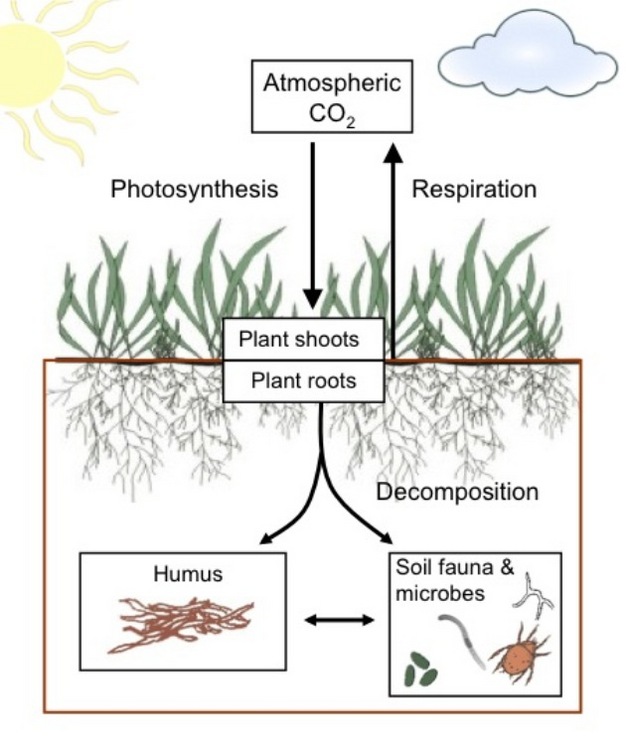

Soils could also be considered a form of climate guardian, holding more carbon than both the atmosphere and all vegetation. Disturbances to soil, like deforestation and poor agricultural practices, can lead to the release of this stored carbon into the atmosphere, contributing to greenhouse gas emissions. Conversely, healthy, well-managed soils can sequester carbon from the atmosphere, potentially mitigating climate change and emphasizing the urgency to manage and protect them diligently (Lal, 2004; Paustian et al., 2016).

The image to the right displays a schematic of potential pathways for CO2 molecule once sequestered from the atmosphere through the soil (Ontl and Schulte, 2012). Carbon balance within the soil (brown box) is controlled by carbon inputs from photosynthesis and carbon losses by respiration. Decomposition of roots and root products by soil fauna and microbes produces humus, a long-lived store of soil organic carbon.

See the recommended video below for an in-depth look at where soil fits into the carbon cycle.

In Conclusion

The soil is not just dirt beneath our feet; it’s an intricate world, pulsating with life! Most importantly, this reminds us of the profound interconnectedness of our planet. Every grain, every microbe, and every root tells a story of life’s incredible resilience and interdependence. Soil ecology, with its myriad interactions and functions, is a cornerstone for the Earth’s biosphere. It is a compelling testament to the interconnectedness of life and a crucial piece of the puzzle in addressing global challenges such as food security and climate change. As we discover the secrets whispered by the earth, we gain insights into addressing global challenges and securing a future for generations to come. So, as you tread the Earth, pause and appreciate the delicate symphony beneath, remembering the vital tune it plays for our planet’s future.

Stay Adventurous,

Olivia Grace

References

Bardgett, R. (2005). The Biology of Soil: A Community and Ecosystem Approach. Oxford University Press.

Bardgett, R. D., & van der Putten, W. H. (2014). Belowground biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Nature, 515(7528), 505–511.

Coleman, D.C., Crossley, D.A., Hendrix, P.F. (2004). Fundamentals of Soil Ecology. Academic Press.

Lal, R. (2004). Soil carbon sequestration to mitigate climate change. Geoderma, 123(1-2), 1-22.

Lavelle, P., & Spain, A. V. (2001). Soil Ecology. Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Mendes, R., Kruijt, M., de Bruijn, I., Dekkers, E., van der Voort, M., Schneider, J. H., Piceno, Y. M., DeSantis, T. Z., Andersen, G. L., Bakker, P. A., & Raaijmakers, J. M. (2011). Deciphering the Rhizosphere Microbiome for Disease-Suppressive Bacteria. Science, 332(6033), 1097-1100.

Ontl, T. A. & Schulte, L. A. (2012) Soil Carbon Storage. Nature Education Knowledge 3(10):35

Paustian, K., Lehmann, J., Ogle, S., Reay, D., Robertson, G.P., Smith, P. (2016). Climate-smart soils. Nature, 532(7597), 49-57.

Ritz, K., & Young, I. M. (2004). Interactions between soil structure and fungi. Mycologist, 18(2), 52-59.

Smith, S. E., & Read, D. J. (2008). Mycorrhizal Symbiosis. Academic Press.

Vasilas et al., 2016: researchgate.net/figure/The-soil-profile-ab-ve-consists-of-an-8-cm-314-inches-layer-of-peat-and-or-mucky-peat_fig1_318239569

Vitousek, P.M., Menge, D.N., Reed, S.C., Cleveland, C.C. (2013). Biological nitrogen fixation: rates, patterns and ecological controls in terrestrial ecosystems. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 368(1621), 20130119.

Whitman, W.B., Coleman, D.C., Wiebe, W.J. (1998). Prokaryotes: the unseen majority. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 95(12), 6578-6583.

Bardgett, R. (2005). The Biology of Soil: A Community and Ecosystem Approach. Oxford University Press.

Wardle, D. (2002). Communities and Ecosystems: Linking the Aboveground and Belowground Components. Princeton University Press.

Fierer, N., & Jackson, R. B. (2006). The diversity and biogeography of soil bacterial communities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103(3), 626-631.

Manzoni, S., & Porporato, A. (2009). Soil carbon and nitrogen mineralization: Theory and models across scales. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 41(7), 1355-1379.

Doran, J. W., & Zeiss, M. R. (2000). Soil health and sustainability: managing the biotic component of soil quality. Applied Soil Ecology, 15(1),

Rutgers, Michiel & Mulder, Christian & Schouten, Ton. (2008). Soil ecosystem profiling in the Netherlands with ten references for biological soil quality. RIVM Report. 60760400. 1-89.