The value of biodiversity is that it makes our ecosystems more resilient, which is a prerequisite for stable societies; its wanton destruction is akin to setting fire to our lifeboat.

Johan Rockstrom

What is biodiversity?

The term biodiversity refers to the multitude of living species on Earth and their incredible variations. There are no exclusions for organisms when describing total global biodiversity, meaning organisms from all three domains of life are included. These domains are referred to as Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukarya. The relationships of these groups can be seen in the image below.

Members of Eukarya include eukaryotic organisms such as plants, animals, protists, and fungi. Archaea includes organisms such as retroviruses, and bacteria includes microbes such as E. Coli (a common cause of food poisoning). Archaea are unicellular organisms that lack a true nucleus (organelle that contains the genetic information of an individual), which distinguishes them from their nucleated counterparts Eukarya and Bacteria. Despite sharing similarities when compared to Archaea, members of Eukarya differ from Bacteria as these organisms are multicellular and have their organelles (functional parts of the cell) surrounded in individual membranes. Members of Archaea are commonly represented by those organisms that live in extreme conditions such as in the Dead Sea (‘salt-loving’ halophiles) or in volcanoes (‘heat-loving’ thermophiles).

Depending on the ecological system being described or studied, the scope of biodiversity might be confined to a particular location or groups of locations. When we describe the biodiversity of organisms at one particular location, we refer to this as an assessment of alpha diversity (α diversity). This measurement is particularly useful for understanding what mixture of species are present within an area.

For example, if you were to measure the alpha diversity of a park in city of Chicago, you may include up to a mixture of 155 species of birds depending on the location of the park, numerous insect species, plant species, etc. Regardless of the type of species, because we have established our area of study as the park, every living species within the park will be included in the alpha diversity assessment.

When multiple locations are taken into consideration, this becomes what is considered a beta-diversity (β diversity) assessment. This type of assessment can be incredibly useful when assessing large regions for biodiversity. For example, β diversity is beneficial for assessing the biodiversity of a country, or a large region of land such as a state. In this application, alpha assessments are taken at many different habitats, and compiled in a beta diversity application.

The scenarios given above for α and β diversities involve looking at an ecosystem level. These terms can, however, be applied to smaller scales, for instance looking at the biodiversity among a certain species (either from observable characteristic or genetic differences).

The video below is a great example at looking at species diversity within ants in the Gorongosa National Park (Mozambique, Africa).

How does biodiversity arise?

Within every organism, there is a sequence of genetic information that makes up every characteristic of that individual. From time to time, sequences must copy themselves in order to create new cells or pass on genetic information. A nature-made machine, editing enzymes are not perfect and occasionally make errors. These mistakes involve either adding in a base pair that doesn’t below (e.g., AATCG becomes AATGCG), removing a base pair altogether (e.g., ACGT becomes AGT), or swapping one base pair with another (e.g., ACCT becomes ACCG). Changes such as these can be fatal depending on the location of the change, or can have no effect on function. Occasionally, errors (also known as mutations) can alter a function within the organism without being fatal, resulting in a change of a visible characteristic. If these mutations are heritable (or within the cells to be used during fertilization), they can be passed on to new generations.

With new genetic potential, if a particular change in function is beneficial to an organism, these characteristics boost this individual’s chance for survival–heightening its chance of passing along this beneficial mutation to more offspring. Over time, accumulation of desirable characteristics in a population begin to shift the genetic pool available during mating events. Through directional selection, or a movement toward a beneficial trait in a population, these organisms become more similar to each other at the sequence where the mutation occurred. Errors in sequencing will continue over time, and those that occur in heritable cells (sperm, egg, etc.) might allow for survival against a new environmental factor, contributing to further shifting in genomic patterns and eventually allowing for the possibility of a new species with unique traits to emerge.

With enough geographic isolation or lack of gene immigration from outside populations, mutations in a population accumulate and eventually can cause populations of what were once the same species to now be genetically distinct enough to be considered different species.

What are the pressures that could shape an organism’s survival?

In the context of mammals, after the mass extinction of dinosaurs in the Cretaceous period (estimated 145.5 million years ago) a wide range of habitats became available for surviving creatures to colonize. One lineage became especially adapted to new modes of life, eventually extending a branch providing us humans (Homo sapiens) the opportunity to wonder about these foundational moments in history.

The video below is an illustration of the new habitats created for ancestral mammals and the selective pressures driving the adaptations needed to thrive in them.

Perhaps one of the most cited examples of colonization into new habitats is a case of adaptive radiation in Darwinian Finches (1800s). The term adaptive radiation refers to the same logic we set forth earlier, stating that organisms that invade available niches will have selective pressures from the environment on traits that encourage their success. Organisms with beneficial mutations or heritable abilities will survive, pass on their genetic information, and in turn a new species of organisms can emerge over time, now adapted to this new habitat.

Below is another HHMI BioInteractive video I recommend on evolution in Galapagos finches observed by Charles Darwin.

What is the significance of biodiversity?

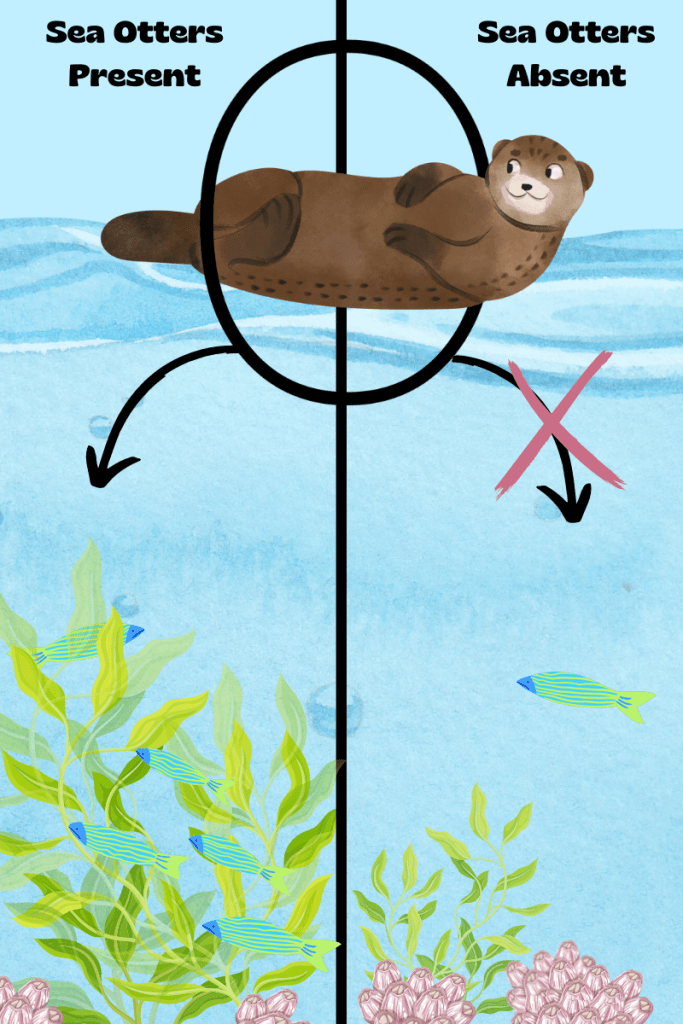

Once biodiversity is established in an area, there are heavy consequences for its collapse. The greatest example of this is with the removal or eradication of keystone species. These organisms are foundational species for an area, meaning their presence keeps the living systems surrounding them regulated. When removed, the ecosystem shortly collapses. One example is the sea otter! As illustrated in the image to the right, when sea otters are present in their environment, barnacle populations remain at low sustainable levels, allowing lush kelp forests to grow and provide shelter for a wide array of aquatic biodiversity. When sea otters are removed from their environment, barnacle populations grow exponentially without predation, resulting in a reduction of kelp forests. Once home to many fish species, without kelp these organisms must find new homes, and as a result are either forced to leave the area or are exposed to predators and collapse themselves.

Non-keystone species also have ecological roles in their environment, which can cause domino effects for species that rely on interactions with them or something they were directly involved with. For instance, some caterpillars are known to take place in what is known as ecosystem engineering. This means the organisms are altering their environment in some way, which in turn can be useful for other creatures. In the case of caterpillars, many will create sheltered burrows in rolled-up leaf material. These burrows remain once the caterpillar no longer needs them, and is then used as a home for many different types of insects.

Regardless of ecological status, all species comprising our global biodiversity contain intrinsic value for their representation of millions of years of evolutionary lineages and evolutionary potential.

How is biodiversity conserved?

At the heart of the drive toward conservation rests governmental policy. Unfortunately, organized citizen by citizen efforts to be conscious about their environmental interactions are limited by the amount of people educational platforms and word of mouth can reach. Only through true government-mediated policy–be that local or federal–will large scale conservation efforts be able to go into effect.

Conservation laws specifically targeting keystone species are incredibly beneficial. Under these policies, not only is the habitat of that keystone species protected, you are in turn automatically conserving the habitat for the other species that occupy the area. The term for this is having an umbrella species, meaning the conservation of one implies conservation of a vast amount of other species. Umbrella species do not always have to be considered a keystone species, but do have to share habitat parameters with other organisms for them to be inherently included in the conservation efforts.

In situations where an organism is dwindling and is not considered an umbrella species, conservation efforts may not benefit other individuals, and thus more efforts may be required to conserve many species in a particular area. To get involved in the politics underlying conservation, it is encouraged to search periodically for bills being presented and contact your local representatives to express desires for the passing of these policies.

Ultimately, awareness within the general public of conservation-related issues and personal, consistent interaction with local government officials is the pathway for driving ecological reform.

Every individual can make a difference in the fight against biodiversity loss!

Ways to Get Involved with Conservation

1) Educate yourself. Stay up to date on current issues in conservation biology. To do this, there are a few options for quick-resources on the latest topics: Eco News Now | Phys Org | Nature Portfolio.

2) Contact your local officials! Stay up to date by searching for current conservations bills being presented to legislators, and make your desires known! To find your representatives, you can use this White House search tool.

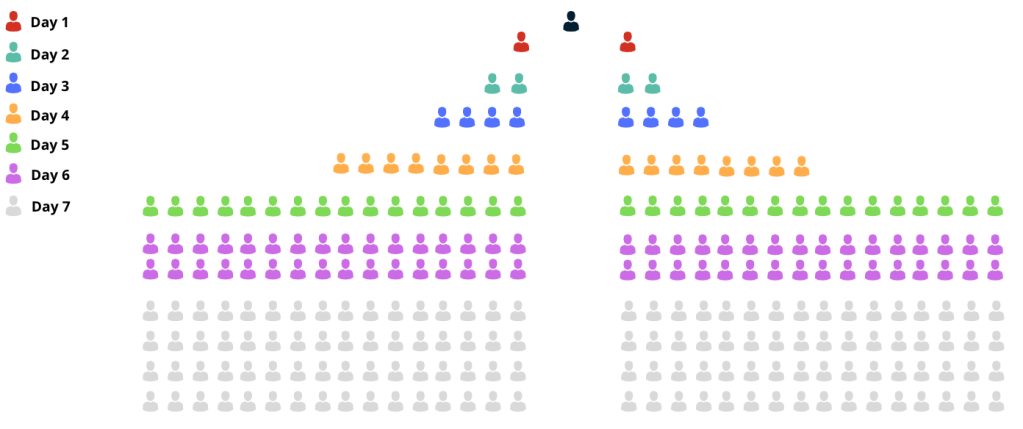

3) Spread Awareness! Even if you cannot contribute at the moment, ambassadorship for conservation biology can spread to someone who might be able to.There is exponential growth with spreading the word! Even spreading information to two individuals on a Monday, if each person tells two other people the next day, you have the potential to have reached 254 people by the end of the week (see the figure below)!

4) Volunteer your time. It is best to make an impactful difference in a chosen area, so be sure to not spread yourself too thin! Many organizations offer volunteer opportunities, such as local preservation chapters and zoos. To find opportunities in your area, quick internet searches are often very effective. To save time, Our Endangered World has created a list of opportunities and subsequent ways to find organizations. Visit this information here.

5) If you do not have time to volunteer, do not fret! There are many ways you can symbolically adopt animals, many of which are housed in zoos and other preservation agencies. Here are examples of symbolic adoption packages offered by WWF (World Wildlife Fund, Inc.).

6) Contribute to citizen science! Getting involved with citizen science projects is an incredible way to experience current research first-hand. One example in Birmingham Alabama, The Urban Turtle Project, allows citizens to help in the capture and counting of turtle species across the state. To learn more about this organization, you can follow this link.

For additional information on conservation biology and the importance of biodiversity, you can view the attachment videos following this article!

Stay Adventurous,

Olivia Grace

Additional Resources: Educational Videos

TEDEd Talk on the Importance of Biodiversity

Crash Course on Conservation and Restoration Biology