How a small farm in northern Vermont is doing its part in saving the world.

Gold Shaw Farm is a small-scale beef, poultry and tree operation located on 150-achre’s of land in the rural northern town of Peachum, Vermont. Founded by couple Morgan Gold and Allison Ebrahimi Gold in 2016, this farm has continuously aimed to operate under the main principles of regenerative agriculture.

No-Till Farming and Cover Crops for Soil Health and Sustainability

Regenerative agriculture is a sustainable farming strategy focusing on the preservation and cultivation of native biodiversity both above and below ground. The foundation of regenerative agriculture can be boiled down to the basic idea that if you take care of something, it will last longer. In this case, the stakes are a bit more severe.

Depending on the environment, the practices of regenerative agriculture can differ, but the main goal of all strategies is to increase the microbial biodiversity in the soil. In terms of current agricultural practices in the United States, the utilization of monocultures, organic or not, have negative impacts on the soils microbial diversity.

In commercial farming operations, monocultures, or the mass seeding and farming of one crop, leads to a decrease in the diversity of native plants, soil, and microbes. In conjunction with monocultures, many commercial farms often will till their soil. Tilling is a process of mechanically turning over the top layers of soil to prep for crop seeding. Several studies have shown that the constant tillage of soil leads to the destruction and death of microbes which leads to a decrease in organic nutrients useful for the plants, resulting in the need for high nutrient fertilizers. Along with a decrease in nutrients, tilling eventually leads to soil erosion. Soil erosion will then result in an increase in chemical runoff into ground water due to the increased usage of fertilizers, which then can further affect the surrounding ecosystem and environment.

In order to avoid the negative impacts tilling has on the environment, Gold along with several farmers around the world have started to revert back to no-till farming. No-till farming is as easy as it sounds, not tilling the top portion of the soil before seeding crops. This preserves and employs helpful organisms within the soil, allowing for proper nutrient cycling. Along with no-till farming, the use of cover crops can increase the nutrient and diversity of the soil. Cover crops are companion plants, used to help increase the quality of soil by for the main crop by breaking up and aerating the soil. In conjunction with organic and natural fertilizers like mulch, no-till farming is a great way to maintain or improve the quality of soil.

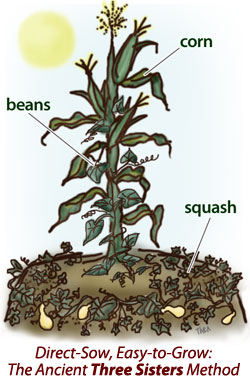

You can practice this type of farming in your own home as well! For those who have outdoor gardens, instead of planting your crops grouped up together, consider alternative planting strategies, and example being the Three Sisters garden. Three Sisters gardens were originally developed by Native Americans. The three crops that this technique is built off of includes corn, beans, and squash. How and when each crop is planted aids in the others crops survival while simultaneously increasing the nutrients available within the soil.

A Solution to Overgrazing and Desertification in the United States

Other regenerative practices include Regenerative Grazing. Currently in the United States, many commercial ranches and farms raise cattle, and/or other ruminates like sheep or goats, in open fields where they are allowed to graze freely. In doing so, these farms actively allow their cattle to overgraze fields of grass, slowly deteriorating the soil causing desertification.

Overgrazing occurs when cattle are allowed to continuously graze on a single patch of land. When this happens, the grass cannot grow efficiently resulting in less growth overall causing the cows to graze more since less grass is available. Eventually, this negative feedback loop results in extremely dry and eroded soil causing desertification.

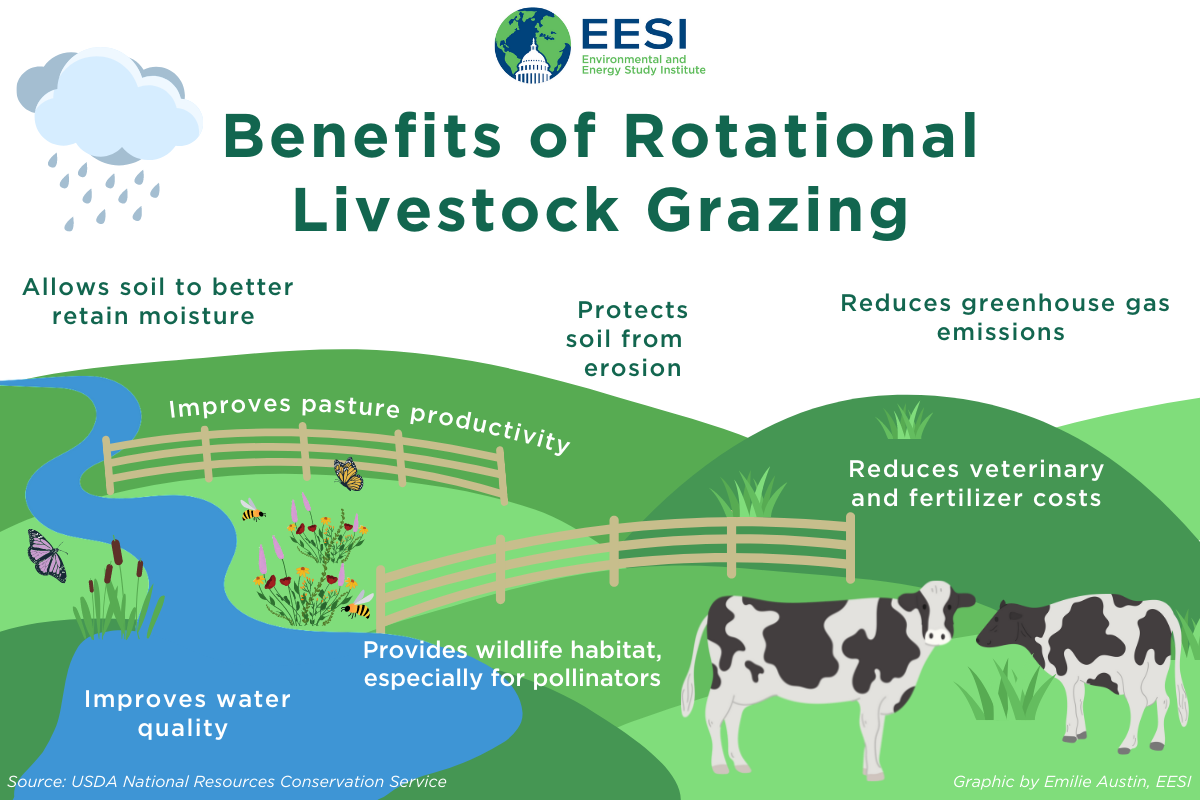

In order to counteract overgrazing and desertification, farmers like Gold have started to utilize old school strategies like intensive rotational grazing. Rotational grazing reflects ruminates natural grazing behavior, where cows would remain in herds and graze in small areas to remain safe. In utilizing this behavior as a farming technique, Gold began to isolate his Scottish highlanders to one paddock where their grazing is concentrated. While grazing, the cattle will also start to fertilize the soil with their manure, aiding in future grass growth. After the grass in one paddock gets eaten down, Gold then moves his cattle to the next adjacent paddock where the process begins again. Once the herd moves from one paddock to the next, they won’t visit the old paddock until grass has been able to fully grow and accumulate high amounts of biomass, usually a cycle of about 60 days.

"I try my best to mimic nature -" Gold says.

The Integration of Trees and Shrubs into Regenerative Agriculture Practices

One last pillar of regenerative agriculture includes Agro-Forestry. Agro-forestry is a set of agricultural practices that integrate food producing trees and shrubs into traditional farming systems. In this strategy, particular attention is given to native plant diversity and ecosystem interactions. There are several strategies to agro-forestry, with the most common one being food forests. Here each layer of the seven layer plant system has some contribution to the health of the whole system.

Another example of agro-forestry are permaculture orchards. A permaculture orchard is basically an ecologically conscious and strategically planted food forest, where trees are planted in plantation like fashion. The defining features of a permaculture orchard begin with the word Permaculture. Permaculture, coined by Bill Mollison, is a the act of consciously designing, building, and maintaining an agriculturally productive ecosystem, or creating a permanent agriculture. Therefore, permaculture orchards are not only for agricultural use, but are designed to serve several functions within the native ecosystem.

Within his 150-arche farm, Gold has been able to create his very own permaculture orchard. Since the beginning of Gold Shaw Farm, Gold has been cultivating native tree and shrub species from Northern Vermont, including hazelnuts, elderberries, mulberries, black locus, and chestnut trees.

Overall, the use of rotational grazing and permaculture orchards can combine to create another regenerative agricultural practice, known as silvopasture. In silvopastures, there is a deliberate interaction with tree and livestock operations, where rotational grazing is used as the key to managing wooded or pastured orchards. Here, as the cows graze they are covered and cooled by shade the trees provide. The trees in turn are protected from any invasive plants or weeds while also being provided nutrients from manure fertilizing the soil. In addition to livestock and orchards, silvopasturing can involve other farm animals like chicken, ducks, and geese, which help to spread manure and eat excess bug larvae left over.

At the end of the day, regenerative agriculture is aiming to save the world by reducing CO2 emissions, decreasing deforestation, improving the quality of soil and increasing the nutrients within the soil. Through entertaining and educational videos via YouTube, TikTok, Facebook, and Instagram, Morgan Gold shares his life on the farm. By utilizing regenerative agricultural techniques such as no-till farming, intensive rotational grazing, permaculture orchards, and silvopastures, Gold Shaw Farm is doing its past in saving the world.

You can follow the adventures of Morgan and Allison on instagram @goldshawfarm.

References

Díaz, S., Settele, J., Brondízio, E. S., Ngo, H. T., Guèze, M., Agard, J., … & Sharma, N. (2019). Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Retrieved from https://www.scienceforbiodiversity.org/assets/docs/ipbes_global_assessment_report_summary_for_policymakers_en.pdf

Natural Resources Defense Council. (n.d.). Regenerative agriculture: 10 practices to regenerate soil and increase farm productivity. Retrieved from https://www.nrdc.org/stories/regenerative-agriculture-10

Permaculture News. (n.d.). What is permaculture? Retrieved from https://www.permaculturenews.org/what-is-permaculture/#:~:text=Permaculture%20(the%20word%2C%20coined%20by,and%20resilience%20of%20natural%20ecosystems.

Smith, P., Martino, D., Cai, Z., Gwary, D., Janzen, H., Kumar, P., … & McCarl, B. (2007). Agriculture. In Climate change 2007: Mitigation. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (pp. 497-540). Cambridge University Press.

USDA National Agroforestry Center. (n.d.). Silvopasture. Retrieved from https://www.fs.usda.gov/nac/practices/silvopasture.php